Are bad markets good for AI agents?

How fast-growing unicorns like Cursor and Glean are speeding up historically slow SaaS categories and what it means for VCs, Saas leaders and aspiring founders

Over the last week, two AI unicorns—Glean and Anysphere (aka Cursor) — shared a compelling milestone: crossing $100M in ARR.

These two companies couldn’t be more different. Glean has over 800 employees and is sold top-down to enterprise IT leaders. Cursor has just ~30 or fewer and has spread bottom-up amongst developers, only hiring their first sales reps last month.

Glean’s founder, Arvind Jain, is a seasoned technologist with a spectacular 25+ year career (Microsoft, Akamai, Google, founded Rubrik in 2014). Anysphere, the company behind Cursor, was founded by four MIT grads who started school in 2018, the year after researchers at Google Brain published the now legendary paper “Attention is All You Need”1.

Glean is only for large collaborative teams; Cursor is for personal productivity. The list of differences goes on.

However, both companies have a couple of things in common: They are both agentic SaaS products and started in what successful investors historically considered bad markets.

An exclusive club: $1 to $100M in <4 years

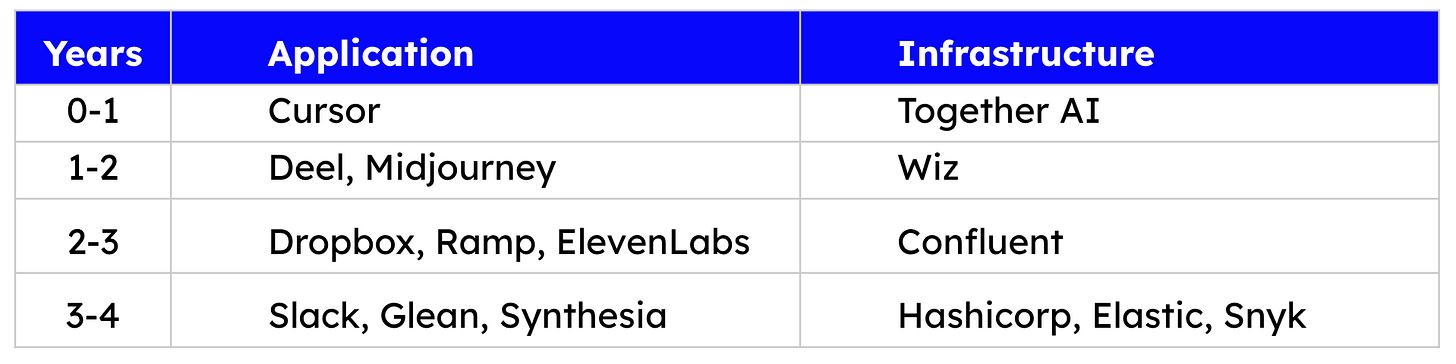

Let’s take a closer look at the exclusive club that Cursor and Glean are members of— 21st-century cloud software companies that grew from $1M to $100M in annualized revenue2 in 10-48 months. This isn’t an exhaustive list, so if you have edits, additions, etc., with primary sources to offer, please share them! And yes, I am extremely aware they have very different gross margins.3

These 15 companies span a variety of markets - from payroll to security and storage. Six of the fifteen are AI startups now - Cursor, Midjourney, ElevenLabs, Glean, Synthesia and Together AI. I expect more (hello Perplexity, Heygen, Mercor, Clay..) to be added to the public list soon. While it remains to be seen which of them will become defensible, generational businesses with the 30%+ FCF margins we see in SaaS, they have all certainly found some product-market fit.

Were these six AI companies started in good markets? To answer this question, we must first consider what makes markets bad for venture. There is some fascinating nuance here and significant implications for both VCs and incumbent SaaS leaders. Stay with me.

What’s a bad market for startups and new products?

OG Silicon Valley investor legends Arthur Rock and Don Valentine had a lot to say about founders and markets. One thing they both agreed on was that even the best founders could be defeated by bad markets.

An obvious bad market is one that simply doesn’t exist - there is no demand for your product - you got the bet wrong. A less obvious bad market is a stale one, with nothing changing in it. However, in the age of AI, almost every market segment is feeling winds of change. These two scenarios are not material to our analysis.

There are more nuanced bad attributes in enterprise software markets that successful VCs care a lot about. They can be synthesized into three groups:

The market is too early.

The market is hard to monetize.

The market has poor LTV/CAC.

Did the markets our 6 new high-growth AI unicorns start in meet these criteria for reasonable investors?

1️⃣ Bad markets can be too small or early

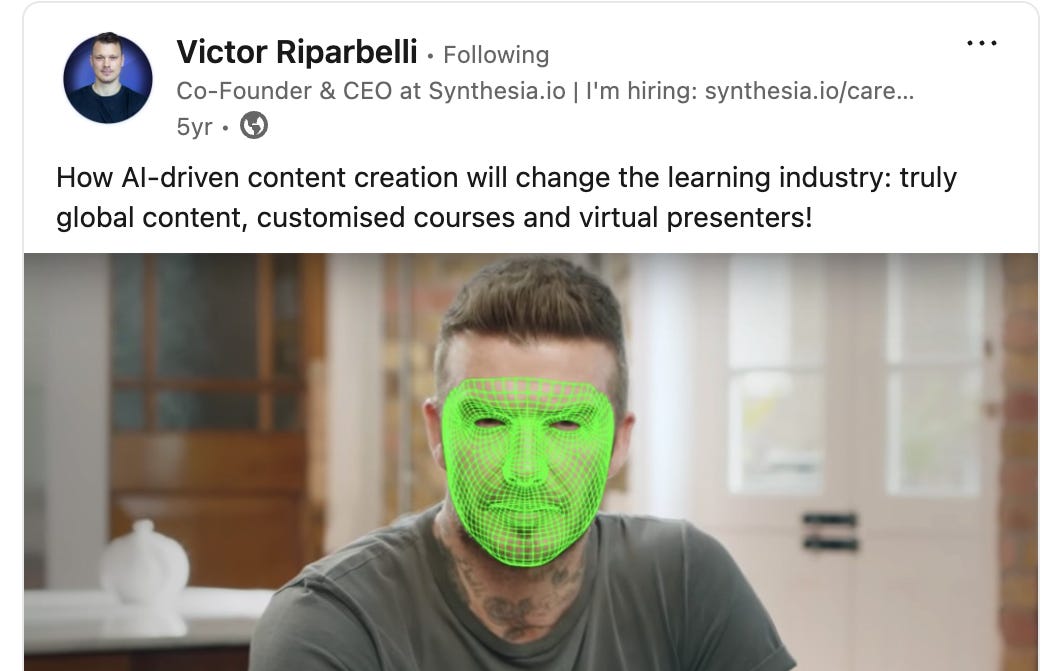

When Synthesia first launched in 2019, there wasn’t much of a market for “deepfakes”, as we called AI avatars at the time. The technology itself was early, and its social acceptance was low. “Video tech” was already being attempted with middling success (Frame, Descript, etc) and didn’t look like a venture-scale market. Synthesia focused on helping small teams dub their content and produce informational videos for employee training and sales enablement, not sexy markets. It took them over 2 years after first launching the product to get to their first $1M in ARR while charging $20/month per seat.

Similarly, when Together AI was founded in June 2022, there were barely any companies with open source LLMs running in production. Does anyone remember EleutherAI’s GPT-NeoX model? Probably not. Llama wouldn’t be launched by Meta till April 2023. No MLOps company with an open source focus had succeeded to date despite billions of VC funding being poured into the category. Moreover, it wasn’t clear why everyone wouldn’t just work with cloud hyperscalers like AWS for fine-tuning and training their LLMs. Neither the market nor the research seemed compelling yet.

The markets for both Synthesia and Together AI were too small and early when they first launched their products.

2️⃣ Bad markets can be hard to monetize

There are many reasons that markets can be hard to monetize. Sometimes, it is cultural - none of us want to pay for the news anymore! In the case of enterprise software, there are three primary reasons markets are hard to monetize:

The alternatives are good and free/open source.

It’s hard to assign an ROI to the solution.

The end users can’t afford to pay for products.

These are the exact three reasons I’d argue Cursor, Glean and Midjourney each started in what can be called textbook “bad” markets.

For the past decade, personal IDEs were just not a venture-scale market. Microsoft made VSCode an industry standard by open-sourcing it in 2015, as well as making it free. JetBrains, a bootstrapped Czech startup, offered the only real commercial alternative. It wasn’t obvious this would change even with the advent of LLMs - after all, Github Copilot (with a free tier) integrated with VSCode. In 2023, I heard repeatedly that there was “no way all these overvalued code-gen startups could compete with Copilot, it already has 100k+ teams using it”.

Glean had a different problem when it started in 2019. Their vision for enterprise search was compelling in terms of user experience, but how do you value the solution as a large company? The closest comparable was Atlassian’s knowledge base Confluence - known to not be their primary revenue driver and often sold bolted-on to Jira. It was too hard to assign ROI to an improvement in productivity that couldn’t be measured. Bad market.

By the time I interviewed Arvind in May 2023 for a podcast, this was finally changing.

Arvind described the shift in how his early buyers were valuing Glean:

Now with ChatGPT, it has struck executives that it’s not "hey, search engine, help me find a document"; the technology can actually answer complicated questions and do work for you. For example, you can ask: "Give me the top 10 customers who are likely to churn" and believe it or not, it's going to figure it out.

This brings us to Midjourney, which was wildly popular with hobbyists as soon as it launched. Image generation was new and fun to play with. By the time ChatGPT launched, Midjourney already had 1M users. However, it wasn’t clear who would pay for these generated images (“certainly not engineers on Discord”) and why. What was the value of a header image for a blog post? Would a content marketer afford to pay much for this? The stock image market was not a good one. There wasn’t a clear business case for AI-generated art, certainly not one that made the cut for a venture-scale market.

Cursor, Glean and Midjourney were hence started in markets that were historically hard to monetize.

3️⃣ Bad markets can have poor LTV/CAC

This brings us to the third major reason markets can be bad. A low LTV/CAC ratio - or the cumulative payout of serving a customer compared to the cost of acquiring them. When a company targets SMB/startup customers, this ratio is often the primary reason VCs will pass on the idea. That’s why the $160B Shopify was not a wildly popular startup when it started fundraising. Startup customers come with light wallets and short lives. Small main street businesses are hard to reach.

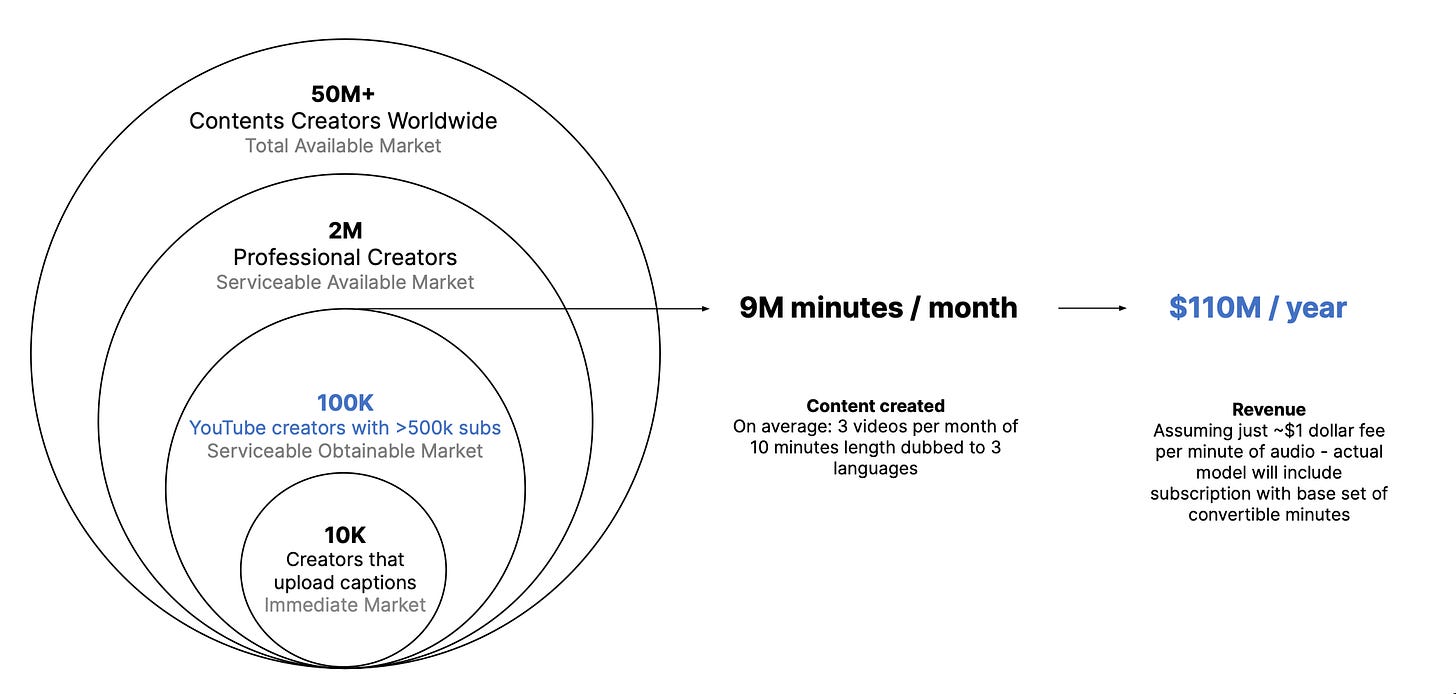

When ElevenLabs was founded in 2022, their focus was on automating dubbing, starting with YouTube creators. They had identified that about 10k of them were already adding captions in languages other than English to reach a broader audience.

For many successful investors, this would be a huge turn-off. The cost of reaching these creators and their willingness to pay might not add up to an LTV/CAC ratio that would get them excited. It is also not a good long-term market because YouTube could do this automatically for free to drive more viewership once Google started rolling out AI features across their product suite.4 Compounding that concern was the question of whether this technology would indeed expand the TAM for audio.

All in all, there were good reasons to be concerned about the addressable market and path to revenue for all six of our hot AI startups in the fastest $1-to-$100M ARR club. Hindsight is 20-20, and once they took off, they became consensus good ideas in great markets.

How’s AI breaking the pattern?

Big technology shifts - semiconductors, internet, mobile, cloud - create new markets that didn’t exist before; this is not unique to generative AI. As everyone embraces a new technology, new problems will be born, and startups will rise to address them.

What’s unique about this wave is that it’s also creating significant opportunities for software to solve problems that are not new at all. They are so old we barely see them as “problems” or “software markets” - they are simply the status quo. From IDEs to dubbing and search, they represent solved problems with well-established, if inefficient, workflows. Some of them have giant near-monopolies dominating the market like Google and Linkedin. I would argue that consumer tech has seen a similar wave after mobile matured, making possible companies like Airbnb, Uber and Doordash - all of which started in historically bad markets. However, enterprise software hasn’t gone through such a wave. So far, winners starting in bad markets have been exceptions in the SaaS and infra playbook. AI has changed that with great pomp and circumstance in 2024.

The startups that are building revenue quickly in these “bad” markets are leveraging the insane, unprecedented attention that AI is receiving from what seemed heretofore like satisfied, well-served customers. Turns out everyone’s work has components that are like folding laundry, and if you there’s a cheap robot available for some of it, laundry becomes a good technology market overnight.

Never before have we experienced a mass willingness to try new things at this scale. Never before have we seen pure word-of-mouth scale SaaS companies to $100M in ARR. Bad markets were avoided because they slowed you down and killed you fast. Being too early was “as good as being wrong”. But what if AI is changing markets so fast and with such heightened awareness that those truisms are now false?

If so, what are the implications?

The implications for VCs are already clear. Those who didn’t take a first principles approach to investing in AI have been left behind, no matter how successful they were in the cloud era. Those who have updated their priors are able to win the right deals before they become consensus.

For SaaS incumbents, the implications are fascinating. Historically, large software companies evaluated funding new projects based on how much of their existing market can be impacted. In particular, they asked, “Will this expand our ACV with existing customers and by how much?” Now, they might need to fund projects that could even decrease ACV at first. It would still make sense as long as it allows them to prevent being disrupted, solve new problems and/or reach customers that were not attractive before at scale. From a first principles pov, TAM expansion is the north star.

Let’s take UIPath as an example. If UIPath builds great, flexible, fully automated RPA 2.0, the natural outcome might be to decrease its ACV with existing customers for their current solutions. It would still have high ROI because it can now serve hundreds of thousands of customers who could never afford to work with them before.

For first-time founders, the implications are annoying - it will always be hard to raise a seed round for what’s considered a bad market. Arvind, being him, raised Glean’s seed round at $40M post-money (in 2019), but the team behind Cursor raised their first round through an accelerator at $5M post-money (in 2022). The best thing to do is to articulate a clear plan for how you can dominate a niche (if bad) market first and then offer multiple ideas for where TAM expansion can come from in the (near) future. If you would like templates or examples of this, drop me a note for future posts!

If you still haven’t read it… SMH: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.03762

Annualized includes annual, monthly and usage-based for the sake of simplicity.

This post is not about gross margins.

Youtube auto-dubbing was apparently launched recently?